Markets are quick to react to change and current events causing them to rise and fall frequently and sometimes substantially. This summer’s double digit decline in U.S. stocks is just the latest example. Such swift declines can add to a sense of chaos and make investors uneasy. As chaotic as markets can be, if we are to get any meaningful return on our investments, we have to be able to adapt to the chaos by taking the prudent action to rebalance accounts.

Rebalancing provides a sound methodology for handling the chaos of the financial markets and can make our investment experience a bit steadier.

The term “rebalancing” can be puzzling because financial markets often seem anything but in balance. It doesn’t make the world safe, politicians smart, the tax code simple, or investment returns steady. Rebalancing provides a sound methodology for handling the chaos of the financial markets and can make our investment experience a bit steadier.

There are many angles and nuances to rebalancing but we will focus on the two benefits we see most prominently: controlling risk and taking emotion out of decision-making.

What is rebalancing?

Rebalancing is the process of buying and selling within a portfolio to keep a portfolio’s structure in line with its targeted mix of investments. Staying aligned with the target is important because the target is established based on client goals. Being too conservative or too aggressive with portfolio structure can be costly and potentially cause the portfolio to fall short of its goals.

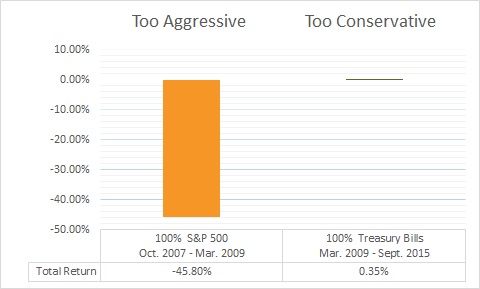

As the chart below shows, being too aggressive can result in significant losses but being too conservative can result in little growth and the loss of purchasing power due to inflation.

Rebalancing can help keep us from panicking when markets are bad and help prevent greed from overtaking us when markets are good.

With the recent decline fresh in our memory, here is a simple example of how rebalancing can help when markets drop.

Assume that in light of one’s goal, we determine that a portfolio should hold half its assets in “A”, a fairly stable investment that has little chance of dropping greatly in value but also with no real opportunity to grow substantially. Cash, CD’s, and good bonds would all be the underlying assets in A.

The other half, “B”, is determined to hold assets in something riskier in the short term, but has good long term growth prospects. Diversified stocks fit this description.

To make the math a little easier to follow, we will use $200,000 in a 50/50 split between A and B with $100,000 in each. A earns 4% while B loses 20%. The total is $184,000 (A=$104,000 and B=$80,000), down 8%.

The portfolio now sports a 57% A to 43% B mix. It is overexposed to the risks and potential return of A and underexposed to the risks and potential return of B. To rebalance, $12,000 of A is sold to buy $12,000 of B, leaving $92,000 in each. The portfolio is back to 50/50.

The investor has lost $16,000 and just bought $12,000 more of the very thing that caused the loss so at this point, how rebalancing provides risk control and a defense against emotional tactical decision-making is not obvious! We will get into the emotional discipline in a moment but first let’s do more math.

Rebalancing and risk control

Without rebalancing and assuming A again rises 4%, A would be worth $108,160 and B would have had to increase to $91,840 or 14.8% for the portfolio to reach the original $200,000.

Because we sold $12,000 of A to rebalance another 4% will only make it worth $95,680. Therefore B must rise to $104,320 to put the portfolio back to $200,000. But, because we bought $12,000 more of B, it only needs to rise 13.39% ($104,320-92,000/92,000).

B will rise 13.39% before it rises 14.8%. By rebalancing, the portfolio recovers faster. In fact, at a rise of 13.39%, the actual price of B would still be off by 9.29% from its starting point when we bought the original $100,000. The portfolio is whole yet the offending holding is barely halfway recovered.

One thing investors crave when experiencing a decline in portfolio value is to erase the loss as fast as possible. Rebalancing will help do that. Despite this, many are anxious about rebalancing because the other thing investors want after a decline in portfolio value is to not lose any more value.

Indeed, if B drops more, rebalancing adds to the losses.

In our example we assumed B recovers after dropping 20%. But what if B drops to 40% of its original price. If we had not rebalanced, A would be worth $108,160 but B would have been worth $60,000 for a total of $168,160, down 15.93%.

So, how much more did rebalancing cost when B had lost just 20%? Mathematically, B dropped another 25% (from $80,000 to $60,000) after its initial 20% drop to get to minus 40% in total. That $92,000 post-rebalancing became $69,000 and A’s portion became $95,680 for a total of $164,680. The rebalancing only reduced total return a mere additional 1.73% to -17.66%.

The fear of a loss could be worse than the actual loss, which leads to some dangerous psychology rebalancing can help us minimize.

Rebalancing can take some emotion out of decision-making

In our scenario, we made no mention of the amount of time between transactions or what happened during the time periods. This could have occurred over an hour, a year, or a decade. Between transactions there could have been a highly contested election, a natural disaster, or a terrorist attack. The tax code could have been completely overhauled. You could have had a major health crisis or lost a spouse. You could have been laid off or promoted. B could have gone far lower or higher or just muddled around. None of that nor anything else changes the math.

The math is simple. To stay on track, you rebalance and doing so when markets decline accelerates your recovery no matter if the recovery is quick or not.

A successful investment experience requires making decisions about an ongoing series of life events in a chaotic world – in real time.

Whether the rebalancing transaction occurs at the bottom, early, or late makes no difference to the math above, but psychologically it presents some challenges. Few will want to “throw good money after bad” or “catch a falling knife” as pundits discuss “head fakes,” “dead cat bounces,” “sucker’s rallies,” short covering, or similar things. If you recall the 2008 financial crisis, these phrases may sound familiar.

Rebalancing after strong markets has benefits too. To use a casino metaphor, it allows one to take some chips off the table and keep some profits. It makes it less likely one will get caught up in the euphoria and “let it ride” or engage in other undisciplined behavior like making bets on highly speculative endeavors with “house money.”

Committing to a sound rebalancing discipline encourages decisions and behaviors which make goal achievement more likely. One’s portfolio largely maintains the exposure to the appropriate risks needed for those goals over the long term while buying a little at relatively low prices and selling a little at relatively high prices.

Buy low, sell high. Rebalancing is a manner of executing that idea without requiring an accurate market prediction. Having a rebalancing discipline can help address some of the emotional aspects of managing a portfolio because one may be less inclined to get swept up in times of hype or dragged down in times of despair.

Buy low, sell high. Rebalancing is a manner of executing that idea without requiring an accurate market prediction.

The core concept is pretty simple but we’ve only isolated one sequence here and are leaving out a great deal more which could be said about rebalancing. There are many nuances and issues to navigate such as when exactly to rebalance, how to manage the tax impact of rebalancing transactions, and how rebalancing between different parts of the world stock markets differs from rebalancing between stocks and more stable holdings, to name but a few. We will cover those in time.

Keep calm and carry on

When conditions are particularly chaotic, we crave control. We cannot control when, or even whether, we are rewarded for risk taking but we can control the types and levels of risks we bear and how we behave when those risks reward or punish us.

In the article, “Rebalancing and Returns,” researcher Marlena Lee aptly said, “The primary motivation for rebalancing should not be the pursuit of higher returns, as returns are determined through the asset allocation, not through rebalancing… Rebalancing decisions should be driven by the need to maintain an allocation with a risk and return profile appropriate for each investor.”

Neither good times nor bad times last forever. Whichever comes next, there will be yet another “next” after that. Having an investment portfolio that is designed to support your goals and is implemented with diversification, discipline, and patience remains the best strategy.

Contact Us

If you have any questions or would like to discuss this further, please give us a call or send us a note.

If you are not a client and you wish to receive emails notifications of new posts – no more than monthly – fill out the subscription information in the sidebar to the right.