December 2010

As we have written in the past, we do not give much credence to the star manager. Their stars usually fade and many that looked skilled were just lucky. When we see a manager outperform their respective category to any significant degree, we immediately get suspicious. The press habitually lauds the approach of the top performers but fails to point out many of the worst performers tried similar techniques.

One of the most common causes of the outperformance – and underperformance – is concentrating the portfolio in just a few holdings. The pitch is that the money is invested in only a few “best ideas”. It is a nice idea with great appeal. Why would anyone buy securities they didn’t feel strongly about? Well, the markets don’t care how any individual feels. But what is often ignored are the greater risks inherent in such a strategy.

A recent presentation by David Booth, the man for whom the prestigious business school at the University of Chicago is named, illustrates how concentration, or the lack of diversification, can make a poor outcome far more likely than a good outcome over time.

Before we get to Mr. Booth’s illustration, we need a quick statistics lesson. Here is a great example from Jim Parker, a VP with the Australian affiliate of a mutual fund firm. Parker pointed out that while the lottery gives one a chance at a great payoff, the odds of success are small. To explain the statistical concept, he described a hypothetical lottery with two million tickets issued at $1 each. All money was to be paid out with the grand prize set at $1 million, second prize was $500,000, two third prizes of $100,000 each, 10 consolation prices of $20,000 each and 10 of $10,000 each.

Two million dollars paid out over 2 million tickets makes the mean, or average, payoff $1. The typical actual experience was far different since 1,999,976 tickets did not pay off at all. The ticket owner lost $1 per ticket. The “outliers”, or extreme outcomes, greatly affect the averages. A better measure of the typical experience is the “median” return. The median is the middle number in the series of outcomes when arranged in ascending order.

Concentrating a portfolio in a small number of stocks exposes a family to more risk and is speculative, just like buying a lottery ticket. A true investor diversifies over many stocks and reduces the effect of the outliers. Diversification reduces risk. It does not improve expected return. In the lottery example, if you bought all 2 million tickets your expected return is still $0 ($2 million in ticket costs offset by $2 million in winnings). However, there is no risk of failing to get that expected return.

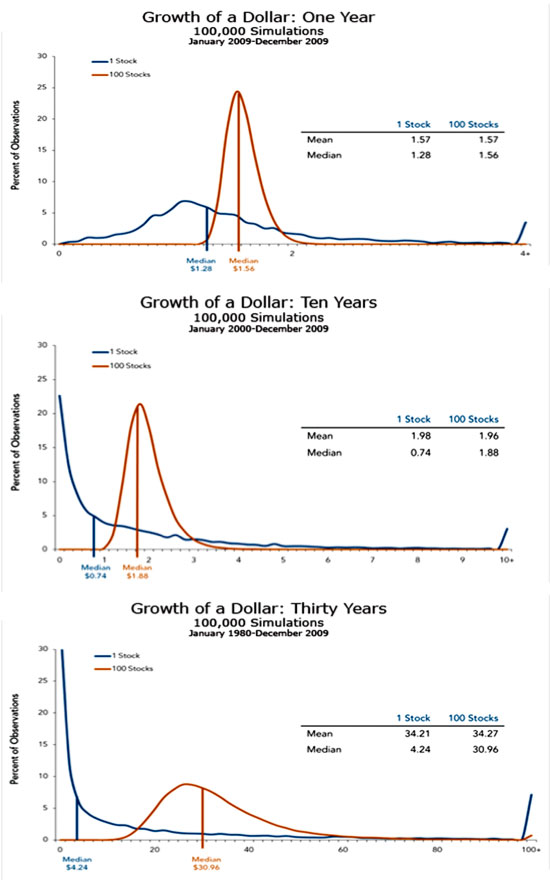

Below are charts from David Booth’s presentation, “A New Look at Diversification”, given earlier this year in Australia. Booth compared the distribution of returns from investing in one stock and portfolios consisting of 100 stocks over one-year, 10-year and 30-year periods in the US until the end of 2009. Thirty years is a common time frame for a new retiree. The portfolios are all randomly selected and the results are based on 100,000 simulations.

The difference in distribution between the 100 stock portfolio (the brown line) and the single stock portfolio (the blue line) is significant over all time frames. The longer the time period, the more damaging the differences become to the typical investment experience.

Notice the median is always lower than the average or mean return and the gap between the median and mean returns becomes wider the less diversified the portfolio. This becomes most pronounced over 30 years. In this case, while there are similar mean returns for all portfolios, the median return (the one most relevant to the individual) is dramatically less in the single stock portfolio, a paltry $4.24 compared with the near $31 median return from the 100 stock portfolio. The spikes at the far-right hand of the graphs are the tiny number of cases where someone was lucky enough to be in a single stock with great returns.

Parker comments, “But that’s like our lottery ticket. You could get lucky, but it’s a one in a million shot. And the fact is you don’t need to take those kinds of risks. By diversifying your portfolio, you might be trading off the remote chance of enjoying that extreme gain, but you are not going to lose your shirt either. This is what diversification is all about. You are reducing the “variance” of expected returns and maximizing your chances of having enough money to retire on. Put another way, you’re taming the luck of the draw.”

We would add that even a 100 stock portfolio is far less diversified than what we typically construct for our clients. This means our experience is more likely to be close to the mean over time. We do not know what that mean will be but we will get almost all of it, whatever it is.

While Booth’s example is a simulation, the concept is hardly new and we have real world experiences to observe. The empirical data supports Booth’s example and Parker’s contention that trying to outsmart the market is a poor strategy. Over the last few decades, studies of actual performance of market participants varied as newsletter writers (Hulbert), individual investors (Barber & Odean, Dalbar), and mutual fund managers (Carthart, Fama & French, Standard & Poors) have clearly demonstrated that the net result for most trying to outsmart the market is a below market result.

Over time, fewer and fewer money managers outperform the markets in which they invest by less and less. For taxable investors, the odds of significantly outperforming on an after-tax basis over a lifetime are tiny. Put another way, if we achieve a result that is close to what the market provides, we are very likely to do better, even dramatically better, than both other investors and speculators.

Having said all this, we are big fans of one type of concentration: the ultimate one stock portfolio – entrepreneurship. In the aggregate, the risks taken by entrepreneurs boost our standard of living and cre ate wealth because most fail but those left standing usually have a superior offering to the public. We prudent, long-term investors are more likely to benefit from the aggregate result – without exposing our assets to catastrophe – by being broadly diversified and staying invested for the long term.

The United States is a free country and you are able to place a big bet on anything or anyone you like. Sure, that clean energy company or tech company setting up shop in China may end up the next great stock, but if you are going to focus on “best ideas”, understand they are more likely to result in a dud of a portfolio than even a modest outperformer.

Contact Us

If you have any questions or would like to discuss this further, please give us a call or send us a note.

If you are not a client and you wish to receive emails notifications of new posts – no more than monthly – fill out the subscription information in the sidebar to the right. For more frequent updates, subscribe via RSS feed or follow us on LinkedIn, or Twitter